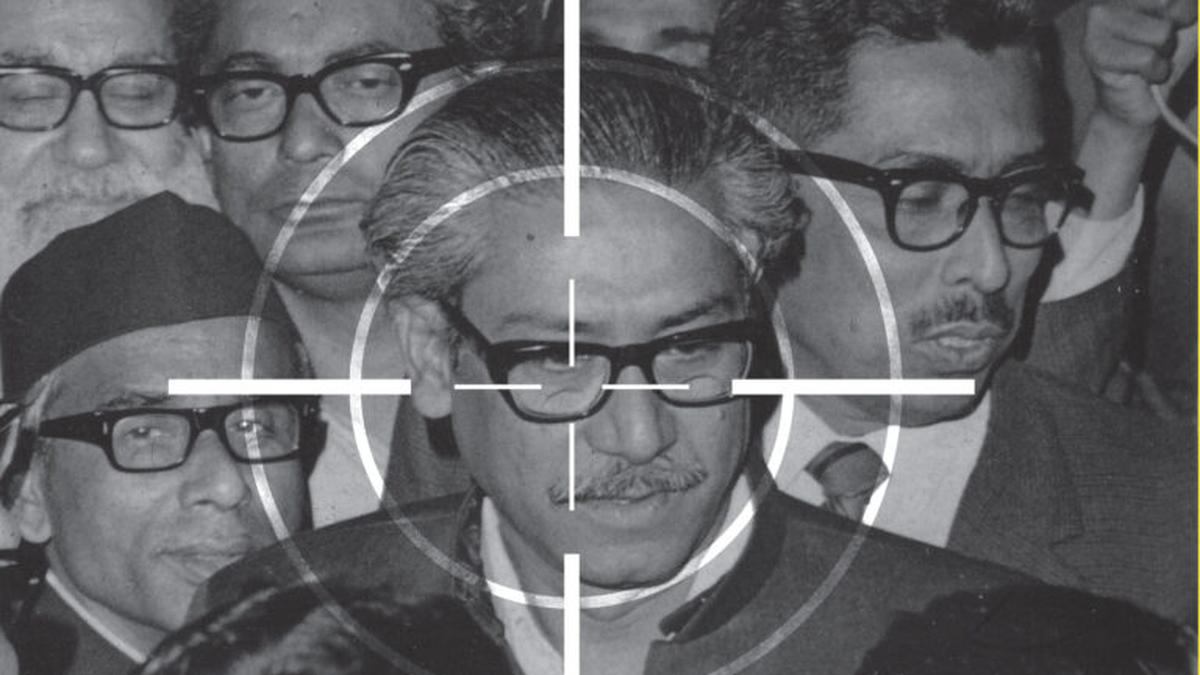

In 1974, a puzzling death in Dhaka set the stage for a seismic political event in Bangladesh, according to a new book by veteran journalist Manash Ghosh. His work, Mujib’s Blunders: The Power and the Plot Behind His Killing, uncovers the mysterious demise of Phanindra Nath Banerjee, a senior officer in India’s Research and Analysis Wing (R&AW), and suggests it foreshadowed the assassination of Bangladesh’s founding leader, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, in August 1975.

Ghosh describes how Banerjee, affectionately known as Nath Babu, was found dead in his room at Dhaka’s Intercontinental Hotel in July 1974. A Calcutta-based joint director of R&AW, Banerjee was no ordinary intelligence officer. He served as a trusted intermediary between Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, carrying sensitive messages directly between the two leaders. His role was critical, blending professional duty with personal rapport, as Gandhi saw Mujib as Bangladesh’s pivotal figure. Banerjee’s frequent interactions with Mujib’s family, including Begum Mujib, and key Bangladeshi figures like Tajuddin Ahmed, gave him rare access to Dhaka’s power circles while he maintained a low profile in diplomatic circles.

The book paints a vivid picture of Banerjee’s significance. “For Nath Babu, building a close bond with a leader like Mujib was key to his success,” Ghosh writes. “But Indira Gandhi wanted that relationship to go beyond work—she saw him as a vital link to Bangladesh’s man of destiny.” This closeness, however, may have made him a target.

Ghosh suggests that Banerjee’s death was no accident. At the time, whispers of a conspiracy swirled in Dhaka. Certain Bangladeshi military officers—colonels, majors, and captains—were allegedly in touch with Western embassies, pushing for a “regime change.” These plotters, Ghosh argues, likely saw Banerjee as a threat. “They probably suspected Nath Babu had caught wind of their plans to target Mujib and his family,” he writes. “With him in Dhaka, executing their plot would’ve been much harder.”

Officially, Banerjee’s death was chalked up to a heart attack, but no post-mortem report was ever made public. Ghosh recalls the eerie silence that followed: “The officer at Ramna police station, the first to arrive at the hotel, told us journalists he’d been ordered not to discuss the case. Bangladesh’s National Security Intelligence officials stonewalled us, refusing to take our calls.” Adding to the intrigue, Ghosh hints that Banerjee might have been poisoned during a meal with a prominent leader from a minority community in Dhaka.

The lack of investigation by either India or Bangladesh only deepens the mystery. For Ghosh and other Indian journalists in Dhaka, Banerjee’s death was a chilling moment that hinted at the violent upheaval to come. His book raises tough questions about who wanted Nath Babu gone—and whether his death was a deliberate step toward the tragedy that would soon befall Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and his family.

.jpg)

0 Comments